Shenandoah University launched an immersive learning initiative this summer that infuses augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) simulation models into teaching and learning experiences to enhance how students learn, first responders train and health care professionals gain new skills.

Shenandoah is exploring AR and VR’s role in learning through both the Shenandoah Center for Immersive Learning (SCIL) and a Technology Fellows program. This immersive training strategy originated with the university’s Shenandoah 2025 strategic plan, which called for a “world-class learning environment” as well as “new financial models for growth” in a rapidly changing education marketplace.

Immersive learning provides faculty with a new way to teach and students to learn. It also allows us to offer new skills for actors, theatre designers and other students as well as develop first-responder and military training, medical simulation and general training scenarios with for-profit and nonprofit organizations.” —Vice President for Academic Affairs Adrienne Bloss, Ph.D.

AR vs. VR Explained

The differences between AR and VR are mostly visual. Augmented reality alters reality, while virtual reality immerses the viewer entirely inside a computer-generated world.

The differences between AR and VR are mostly visual. Augmented reality alters reality, while virtual reality immerses the viewer entirely inside a computer-generated world.

“Augmented reality shows you something virtual positioned in the real world,” technology writer Russell Holly writes in a March 23, 2017, Mobile Nations blog post. “It uses a display — i.e., a cell phone, tablet or laptop — through which you can see the physical world with virtual things — graphics or moving images — added in.” Think playing Pokemon Go. Virtual reality, on the other hand, immerses participants in a digital landscape, where the experience happens entirely inside a computer-generated world.

“Virtual reality refers to any technology that completely replaces what our eyes can see with something else,” Holly writes. “It uses displays and lenses…that cover…your entire field of view. As you move your head, the image moves just as it should in real life, but the images you see are very different from the world around you. This is great for gaming or storytelling, as it allows the viewer to fully immerse themselves in what is happening around them, but it does also mean there’s some disconnect when you accidentally bump into something in the real world.”

Shenandoah Center for Immersive Learning

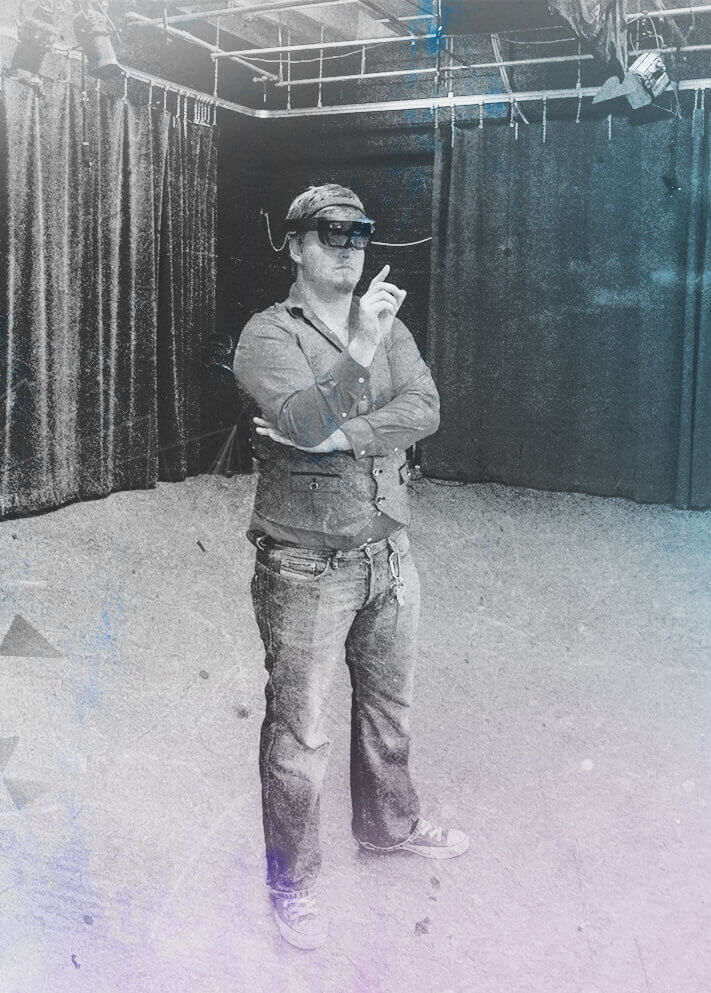

University leaders tapped Associate Professor of Theatre J.J. Ruscella, M.F.A., to pull existing academic and technological components together under the auspices of the Shenandoah Center for Immersive Learning (SCIL), with Ruscella at the helm as executive director.

SCIL evolved quietly, renovating and adapting studio spaces in the Vickers Communication Center on main campus and the Feltner Building in downtown Winchester.

The SCIL lab incorporates AR and VR solutions using three interacting components: an Augmented Reality Chamber (ARC), the Emergency Preparedness Instructional Center (EPIC), and the Role-Player Workforce (RPW). Using a massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPGs) approach, participants live inside virtual worlds, and these gaming modules can be transformed into a training university with learning modules.

The Augmented Reality Chamber (ARC) offers three primary technology components: the Chamber (which focuses on the limitations of the room where a potential learner exists); the Portal (which is the live transportation of participants into shared learning spaces); and the Online Platform (which hosts the online training modules that live in the virtual university). These allow for virtual training that can take place anywhere, any time. The sensors in the Chamber transport participants through the VR portal into shared learning spaces where both trainer and trainee can co-occupy multiple locations.

“The immersive training applications created through the ARC have profound potential impact across countless industries from corporate to governmental, and offer global accessibility, standardization of learning, reduced development cycles, review and archiving ability, time flexibility and approved learning effectiveness,” said Ruscella.

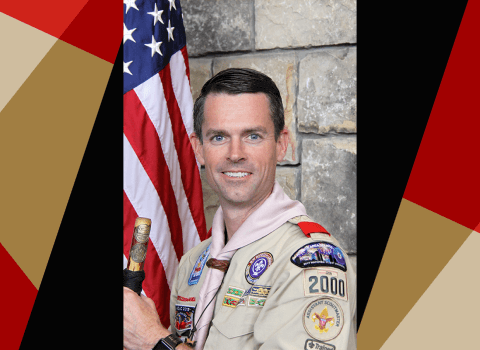

The Emergency Preparedness Instructional Center

(EPIC) will meet the need for first responders to gain the necessary training for active shooter scenarios. It provides best-in-class experts with the latest techniques for law enforcement, emergency management systems, school systems, hospital systems and government agencies. It will include tactical medical training and seminars for rescue task force programs for natural disaster and other first responder training programs.

(EPIC) will meet the need for first responders to gain the necessary training for active shooter scenarios. It provides best-in-class experts with the latest techniques for law enforcement, emergency management systems, school systems, hospital systems and government agencies. It will include tactical medical training and seminars for rescue task force programs for natural disaster and other first responder training programs.

EPIC will use live and virtual scenarios and is the first-of-its-kind training program focusing on medical deployment during active shooter and disaster scenarios,” said Ruscella.

The Role-Player Workforce (RPW) will develop to meet the needs of immersive learning. “Law enforcement and healthcare communities need role-players who represent different ethnicities, backgrounds and perspectives,” said Ruscella. “Role playing can be a vibrant source of income for actors.”

First Immersive Learning Courses Offered

Director for Transformative Teaching and Learning Anne Marchant, Ph.D., facilitated a group of 14 initial Technology Fellows who collaborated with Ruscella this summer to research and explore solutions for adapting immersive learning technologies to complement existing pedagogies.

“It was very much a pilot to see what kinds of AR and VR technologies would be successful at Shenandoah,” said Marchant. “We identified technologies and workflows that could efficiently and cost-effectively enhance students’ learning experiences.”

The Technology Fellows program was first initiated in June 2017 by the Office of Academic Affairs to encourage faculty to participate in a collaborative learning community and develop learning modules using AR, VR, and land, air, sea robotics (LASR), including drone technology, which Marchant incorporated into her First-Year Seminar class this fall.

The initiative was funded by the university and a $30,000 VFIC Special Gift to kick start the project and to add resources to the online digital collection at the Alson H. Smith, Jr. Library. The university used the funds to purchase an array of technology devices, from HTC Vive, ZenFone AR HoloLens and Oculus Rift+touch+Sensor, to 360 cameras and assorted gear, monitors and software.

Immersive Learning in Action

Several faculty have already piloted immersive learning in their courses this fall, with more to launch later this academic year.

Visiting Assistant Professor of Hispanic Studies Casey Eriksen, Ph.D., uses Google Cardboard and Google Expeditions in his “Around the World Through Virtual Reality: Place, Travel, and Cultural Studies in the Contemporary Spanish Language Classroom” class. Using a set of goggles and a mobile phone, students can visit locations online and produce cultural travel diaries in Spanish as they reflect upon the sights, venues, and geographical and cultural diversity of Latin American cityscapes and landscapes. Because he teaches more than one section of Intermediate-Level Spanish (SPAN-201), Dr. Erickson can simultaneously teach one class with VR-enhanced learning tools and the other in a traditional manner.“This will allow me to compare, contrast and assess student comprehension, engagement and outcomes in both VR-enhanced and traditional settings,” said Erickson. “I plan to synthesize these findings into a scholarly article on teaching/pedagogies.”

Assistant Professor Respiratory Care Melissa Carroll-Wood, M.H.Sc., RRT, adapted a QR-code program developed by the University of Wisconsin, where students can use QR codes through their iPads to connect to a taped simulation while engaging simultaneously with simulation mannequins at the Health & Life Sciences Building and Scholar Plaza, Loudoun. “In the past, I’ve done simulations without QR codes,” said Carroll-Wood. “It’s easy to use, and it feels real to them.”

Assistant Professor Respiratory Care Melissa Carroll-Wood, M.H.Sc., RRT, adapted a QR-code program developed by the University of Wisconsin, where students can use QR codes through their iPads to connect to a taped simulation while engaging simultaneously with simulation mannequins at the Health & Life Sciences Building and Scholar Plaza, Loudoun. “In the past, I’ve done simulations without QR codes,” said Carroll-Wood. “It’s easy to use, and it feels real to them.”

Assistant Professor of Physician Assistant Studies Erika Francis, M.S., created a virtual simulated operating room demo to encourage students to learn remotely within an immersive clinical environment. While not yet completed, her proof concept demo uses a camera to simulate clinical skills in operating rooms at virtual clinical sites. Students can enter the space, scroll around through the room, and interact with actors who portray holographic patients and medical practitioners within the virtual operating room or intensive care unit. “A lot of PA work is in the OR or ICU, but we can’t take students there,” said Francis. “They’re sterile environments for patient safety. However, we can use this tool for clinical classrooms and rotations, and some of the clinical sites can use it, too. It can be expanded to other health professions programs, as well.”

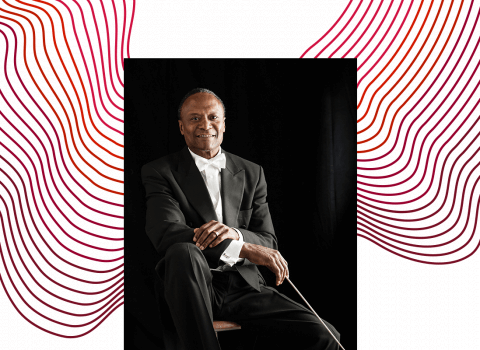

Director of Graduate Music Therapy Studies & Associate Professor of Music Therapy Anthony Meadows, Ph.D., says high-quality video of music therapy sessions is rare, mainly for confidentiality reasons, which impacts students’ ability to gain in-depth understanding of what actually happens in sessions. This summer, using an InstraPro360 camera, he coordinated with musical therapy clinical programs to create immersive session experiences, recording music therapists in a children’s hospital, adult hospice, a memory care unit and in private practice with children with disabilities. “We recorded in true 3D, so students can view sessions from the perspective of the therapist or client, moving around the room while doing so,” said Dr. Meadows. “These recordings include an interview with the music therapist about the sessions, to add further depth and to help student music therapists’ understand the context of the sessions.”

Students Gain New Skills

Senior acting majors Tony Matteson Jr. ’18 and Trevor Ontiveros ’18 worked this summer to help prepare a lab space in the Vickers Communication Center, and in the process explored the new technology.

Senior acting majors Tony Matteson Jr. ’18 and Trevor Ontiveros ’18 worked this summer to help prepare a lab space in the Vickers Communication Center, and in the process explored the new technology.

“We wanted to do a project using the HoloLens, so we created a virtual tour inside this building,” said Matteson. “We spent a lot of time learning the technology and what it can do. Ideally, I’ll be able to design a set in my computer and then put it into the HoloLens, so directors and other set designers can view it, full-sized, before it’s built.”

“And that can extend beyond the stage,” said Ontiveros. “If you want to construct a new building, say a parking garage, you would be able to build it in the virtual world and walk through it with the HoloLens.”

“The industry is now pushing AR and VR not just in gaming but in design, so to know how to use these types of programs will give us a leg up in the real world,” said Matteson. “It also helps in motion capture or green screen work. As artists, we already have over-imaginative minds, but now we can see our creations come to life. It also pushes the envelope when it comes to thinking what we can do once we realize the capabilities of the HoloLens, Oculus and Vibe headsets.”

Matteson and Ontiveros also imagine the possibility of developing a VR program that would allow health professions students to scan a human body and peel away layers to pinpoint a problem. “You could go through a digital surgery, and make sure that it will work instead of injuring a human because of an error,” said Matteson.

Endless Possibilities

The educational industry must adapt to the immersive technologies, otherwise it’s not going to be able to keep up with expectations of its consumers. The unknown for how we apply that technology for education is the new frontier.” —Associate Professor of Theatre J.J. Ruscella, M.F.A.

SCIL will publish a website of its services on su.edu in the months to come. To learn more about immersive learning at Shenandoah University, contact jruscella@su.edu.