Shenandoah University’s debate team and their coach did something extraordinary this year.

They knit together a group of 10 unseasoned debaters from across the university — most without any previous debating experience — and honed their skills through trial and error and old-fashioned determination. Their efforts, while humble in the beginning, earned Shenandoah a growing reputation within the debate community, a national championship at the end of their inaugural season, and a solid base from which to grow the team next year.

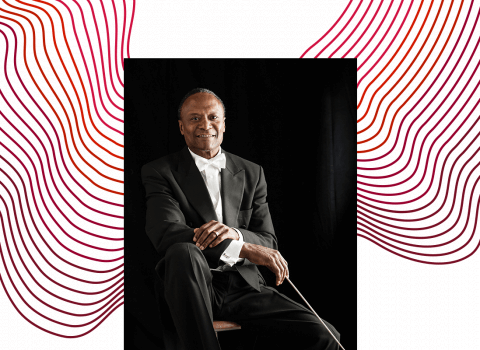

Visiting Instructor of Mass Communications Matthew Corr, served as coach and catalyst, attracting a diverse group of individuals to the team.

“The students came from everywhere across campus, from biology, business and nursing to psychology and mathematics,” Corr said. “It was an interesting mix with a unique chemistry. We became a family.”

Team members included recent May graduates Daniel Hillgren ’17 (business administration), Matthew Laird ’17 (business administration) and Zadok Miller ’17 (team captain, nursing); rising senior Arun Thottakara ’18 (psychology); rising juniors Jonathan Kowiatek ’19 (chemistry), Lora-Maria Koytcheva ’19 (biology), Josiah O’Sullivan ’19 (biology) and Andrew Sartain ’19 (exercise science); and rising sophomores Benjamin Crowder ’20 (nursing) and Grace Eberly ’20 (biology).

Humble Beginnings

“I took a class with Matthew Corr, who said it would be great opportunity for me, with low commitment and high reward,” said Hillgren. “I told him ‘I’ve got a lot going on, but I can probably fit this into my schedule.’ Little did I know it would become such big part of my senior year.”

“I came in with zero experience straight out of high school,” said Eberly. “I’d never debated before, so when I was asked to join the debate team, I was unsure. I was one of two girls traveling in a car [to competitions] with a bunch of guys. It was challenging to adjust to that, but it ended up being a very good experience.”

Each team member brought unique talents and diverse perspectives to the process, and they learned a lot of lessons through trial and error, fixing problems collectively as they worked through the learning process.

“Zadok and I did so badly our first debate,” said Hillgren. “We got last place in our division. It was humbling.”

But afterward, they sat down to dissect their performance and learn from the experience.

“None of us were great public speakers or logical reasoners, but we had people able to research and figure out the best ways to approach the problems in a reasonable manner,” said Hillgren. “It was a team effort and a combination of everything coming together that made us work so well together.”

New Team Rising

Corr said he saw his role as more as a facilitator and encourager than a coach.

“I showed them the big picture and let them run with it,” he said. “I gave them the topic, and they figured it out on their own. [Team captain] Zadok [Miller] took the reins, leading practices and the research team. He only came to me when there was a sticking point.”

“If we started debating a topic where we didn’t have a lot of background, Matthew would just let us figure it out for ourselves,” said Koytcheva, who was drawn to the team as a fun, extracurricular program that fueled her passion for learning. “He played such a vital role.”

“He told us that if we wanted to win, we were going to have to come to practice and put in maximum effort; it was the only way for us get better,” said Hillgren.

“He was very subtle in what he did, but he had a lot of influence in encouraging us to keep going when we didn’t think we could,” said Eberly. “He was more of a guider and leader to show us that we could do it on our own.”

Finding Their Way

The team chose to compete in the National Education Debate Association (NEDA), a collegiate debate association that emphasizes audience-centered debate, using lay judges and focusing less on courtroom-style debate and more on real-world-style logic. In competition, each coach also serves as a judge.

Shenandoah’s team traveled a lot, often driving five to nine hours to competitions and competing with much larger Division I schools, like Ball State University (Indiana), California State University/Fullerton, Wayne State University (Michigan) and several others.

Shenandoah organized itself into five two-member teams. In competition, each was given three debates for the day, a topic and a stance on a policy debate. They were responsible for sourcing research for their side of the debate, quickly gathering their thoughts, and bringing that information into each debate.

“We showed up at a debate with anywhere from 16 to 32 teams,” said Eberly. “We were the smallest school, but we also came with the largest team. So it was different, showing up where we were the smallest school; but coming out, they knew we could stand with them.”

In spring 2017, the debate topic was whether the federal government should substantially reduce its dependency on fossil fuels.

“We debated that topic all semester,” said Eberly. “We debated it out, and we ended up going into semifinals and sweeping the boards. Finals got eliminated because Shenandoah couldn’t debate against its own teams. So we ended up with first, second, third, fifth and seventh trophies at Nationals [at Anderson University near Indianapolis, Indiana]. We debated our best, and because we worked so hard, we didn’t have to debate in the final tournament.”

Learning From Success

In reflecting on their surprising win, Eberly said the team was shocked and elated when they discovered they had won the national title.

“It was amazing!” she said. “Matthew was coaching — you judge and coach at the same time — and the head of NEDA came out and said, ‘I think your team is really happy now.’ He didn’t know that we were outside losing it because we had won a national title for the first year, first semester, unexpectedly. He was so excited. We were just speechless because we didn’t know how to react.”

Hillgren said he thinks the team did so well because they worked on developing each other.

“Everyone likes each other; that’s the best way to sum it up,” said Hillgren. “After each debate, six rounds of tournament play, nobody was saying, ‘we just did so good.’ It was ‘how did your debate go? What can I learn from you?’ We just care about each other.”

In their first year, members of Shenandoah’s debate team learned how to express themselves clearly and articulately. They learned how to listen, how to refine their points and how to prepare for arguments. They also learned that effort and humility breed success. They learned about resources that not only prepared them for competition but for a lifetime of success.

“I just don’t want them to lose the camaraderie, to not get caught up in those accolades,” Hillgren said. “That’s what kept me going this year. Yes, you want to earn those trophies, but you don’t want to lose what makes this team special. Going on these nine-hour car trips and staying in hotels with these folks, you have to like each person. That’s what makes this team special.”

When asked how she would encourage others considering joining Shenandoah’s debate team, Eberly said, “I would tell them it was a great experience. You have to be able to think on your feet. Think fast. Have your research memorized. But it’s a lot of fun, and it’s a great experience that helps you for the future.”

“If anyone is interested in the idea of engaging other people in a debate, not to be right, but in order to learn or find some truth for yourself, this might be good for you,” said Corr. “We have a lot of fun.

To learn more about Shenandoah University’s debate team, email mcorr@su.edu.