Philadelphia resident Harriet Johnston discovered a box of letters buried in the closet of a relative. They were written by Union Army Private Robert Bradbury, who fought in the Northern Shenandoah Valley.

Philadelphia resident Harriet Johnston discovered a box of letters buried in the closet of a relative. They were written by Union Army Private Robert Bradbury, who fought in the Northern Shenandoah Valley.

As fascinating as the documents are to her family, she wanted them to be in good hands after all this time sitting in a box in the dark.

Johnston recalled seeing Shenandoah University professor Jonathan Noyalas speak in 2014 at a re-enactment of the Battle of Cedar Creek, where her own ancestors served in the Union Army, and thought he might be a good candidate to take on her proposal.

Noyalas, who is also the Director of Shenandoah University’s McCormick Civil War Institute, says he wasn’t sure just how many letters were in the collection Johnston had.

“I thought it might have been maybe two or three,” he said.

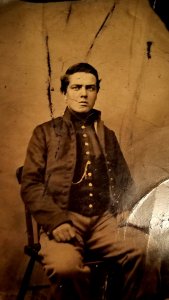

Instead, he got a treasure trove. Dozens of letters, photographs and even a self-portrait of Bradbury were packed into boxes.

“I’m not often rendered speechless,” Noyalas said. “But this was one of those jaw-dropping moments.”

It’s not just the volume that sets this collection apart. It’s the content.

Bradbury, who was just 19 at the start of his service, dropped out of school after the eighth grade according to Noyalas. Yet all of the letters contain descriptive and moving prose, detailing life as a soldier to his sister back home in Pennsylvania.

“If this rebellion succeeds, the nation is [ruined] and the torch of liberty extinguished,” reads one letter.

Others regale the reader with descriptions of a kitten wandering the camp or of a shelter constructed by Bradbury and other soldiers, providing a bit of comfort to them at camp. Another carefully folded letter carried a blade of grass, a souvenir picked from the lawn of the White House.

“To my mind it’s not all bullets and bayonets, gory tragic details of war,” Johnston said. “He talks about what they do, very specifically on an every day basis.”

For his part, Noyalas says he’s spent his life reading soldiers letters and waiting for a moment like this.

“For every 50 letters you read, if you find two or three really great ones,” he said. “There are about 30 letters here. They’re all really great rich content.

But if Noyalas has been waiting for these sort of letters, the reverse can be said for the letters, Johnston believes.

“It just seems the letters have been waiting to find their way to him,” she said. “Because I know they will be carefully annotated, and appreciated and students will have a chance to work with them and then they will be available for others.”

Noyalas already has plans for the documents to be carefully copied, digitized, and eventually published in a book, before being preserved in the University’s archives for future scholars.