The Barzinji Institute for Global Virtual Learning: A Legacy of Dr. Jamal Barzinji

Younus Y. Mirza, Ph.D., recounts the origin and evolution of the Barzinji Institute for Global Virtual Learning

By Dr. Younus Y. Mirza

“Respect for humanity is the foundation of all interaction.” – Dr. Jamal Barzinji

In this article, I will share the history and development of the Barzinji Institute for Global Virtual Learning and how it has actively worked to live out Dr. Jamal Barzinji’s legacy. Through its various programs and initiatives, the Barzinji Institute has intentionally sought to continue Dr. Barzinji’s legacy of intellectualism and activism. Instead of simply writing about Dr. Barzinji, the institute has focused instead on consistent and sustainable programs that put his ideas into action.

Emerging Out of the 9/11 Climate of Fear and Mistrust

First, the Barzinji Project emerged out of a post 9/11 climate of fear and mistrust between “Islam and the West.” After that tragic day, Dr. Barzinji participated in various meetings with government and political leaders to help explain that Islam as a religion was not the source of the attacks. I personally remember Dr. Barzinji giving a Friday sermon (khutba) shortly after 9/11 explaining the true essence of Islam, which was recorded by major media stations like CNN. Dr. Barzinji would eventually meet with then-President George W. Bush to help articulate America’s stance that it was not at war against Islam. To help further clear this misunderstanding, Dr. Barzinji and the International Institute of Islamic Thought (IIIT) worked with various universities to endow chairs of Islamic Studies and programs of interfaith understanding, such as the ones at George Mason University and Hartford Seminary¹. Dr. Barzinji was the president of IIIT at the time and was adamant about investing more resources in the United States and with mainstream educational institutions and organizations, especially those in higher education.

The 9/11 attacks fueled an already strong movement of Islamophobia which continued to gain momentum in the years ahead. Despite the tremendous efforts of Muslim American organizations to better explain Islam and their communities, large portion of Americans continued to harbor fear and mistrust of Muslims, mainly because they relied on media and entertainment for their information. A key factor of whether a person has Islamophobic views is whether they had ever met a Muslim, which many Americans never had. This Islamophobia movement reached its climax with the election of then-President Donald Trump, who campaigned on the “Muslim Ban,” which specifically targeted Muslims, especially those from Muslim-majority countries. In many ways, the “Muslim Ban” represented the opposite of what Dr. Barzinji advocated, such as the belief in harmonious relationships between American and Muslim-majority countries, a global understanding of the world, and (higher) education as a means for social transformation.

¹ Other chairs and programs that Dr. Barzinji worked on were Nazareth College in Rochester, Western Ontario University in Canada and San Jose State in California.

The Emergence of the Barzinji Project

Unfortunately, Dr. Jamal Barzinji passed away in 2015, leaving his family and friends to discuss how they should preserve his remarkable life and legacy. The group was represented by my father, Dr. Yaqub Mirza, who had discussed firsthand with Dr. Barzinji what he wanted in terms of reform of education in Muslim majority countries and had worked closely with him on the various university projects. Dr. Mirza had become a Shenandoah University (SU) trustee and felt that SU would be able to continue this legacy, especially in it being nimble, teaching-focused and entrepreneurial. He approached Shenandoah President Tracy Fitzsimmons, Ph.D., in 2016, to discuss the various options, since she had met Dr. Barzinji several times and had gotten to know him fairly well. Collectively, they came up with the “Barzinji Project for International Collaboration to Advance Higher Education,” which would work on reform of education with a special focus on Muslim-majority societies. The original proposal stated, “Together, participating universities will explore issues surrounding higher education reform in a range of political, cultural, and economic environments, recognizing that globalization requires higher education institutions to collaboratively develop best practices that are effective in various local contexts, prioritizing cross-cultural communication as a tool for co-construction.” Key to the project was embracing Dr. Barzinji’s belief that higher education was a means for social good and that it should have a global and collaborative focus. The Barzinji Project thus adopted his quote that “respect for humanity is the foundation of all interaction” as a key building block and embraced his legacy as an “intellectual education and community builder who advocated for collective action on pressing contemporary issues.”

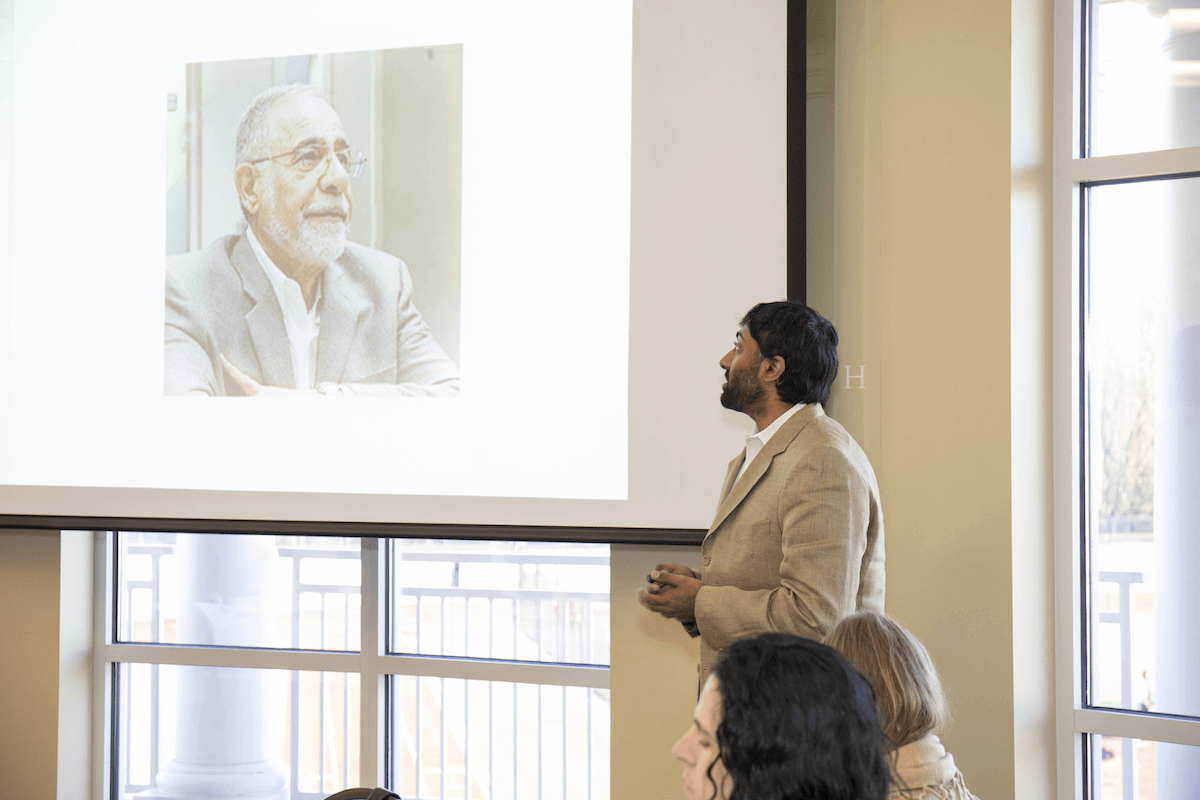

Caption: Dr. Barzinji and Dr. Mirza speak about reform of education in Woodstock, Virginia, located in the Shenandoah Valley.

I was eventually hired as the first project director in 2018 by then-Provost Adrienne Bloss, Ph.D., who was a key formulator and advocate for the project. At the time, I was on a pre-tenure sabbatical at another college, but becoming director of the Barzinji Project was appealing because it was an opportunity for me to help live out Dr. Barzinji’s legacy, as he was somebody I knew personally, respected and liked. As noted above, I had grown up listening to his sermons and had even was a teaching assistant for one of his classes regarding the higher objectives of Islam. As a child, I remember experiencing his hospitality by going to his house for dinners and seeing him serve food to his guests. In particular, I admired his ability to be an intellectual and community builder simultaneously and to always keep in mind the connection between theory and practice. Moreover, leading a truly global project was exciting (especially in an era of nativism), and combating Islamophobia through in-person exchange had always been a key part of my pedagogy.

Selecting Partner Institutions

Among our first tasks was to identify the international schools that we were going to work with, and we selected two schools that Dr. Barzinji had a relationship with: the University of Sarajevo (UNSA) and International Islamic University Malaysia (IIUM). Specifically, Dr. Barzinji was a dean at IIUM and had lived in Malaysia for a couple of years with his family. Additionally, part of thought process was to choose universities in countries that were not stereotypically considered part of the “Muslim world,” as many Americans are unaware that Bosnia and Malaysia have Muslim-majority populations. The two universities would allow participants to compare education in Muslim-majority countries but in vastly different contexts, one in Europe and the other in Southeast Asia. Furthermore, we sought to pick universities that were indigenous to the region and not “western” or “American” implants. Dr. Barzinji was adamant about working with local institutions and organizations, seeing them as having close contact to the grassroots and not simply those which are elite and in an ivory tower. While there are many branches of American universities around the world, the Barzinji Project was intentional in choosing institutions that developed indigenously and were well-integrated in the region.

Caption: Dr. Barzinji was a dean of IIUM, which is pictured here with SU and Bridgewater delegates.

The Barzinji Project then developed delegations made up of faculty, staff and students to visit the partner institutions. This structure is similar to Shenandoah University’s Global Citizenship Project, which sends Shenandoah groups all over the world for spring break trips. Our partner institutions developed delegations with a similar makeup, and we first hosted them at both Shenandoah University and our U.S. partner, Bridgewater College. Through the visit, they learned about key initiatives that the Virginia institutions were working on related to civil discourse or fostering positive discussions in society. The U.S. delegates then visited UNSA and IIUM and, in turn, learned about how the universities worked to preserve their history and institutional memory and formed a unified mission statement. The visits culminated in a fall colloquium in 2019 where the various delegates shared their experiences and discussed future collaborations.

Caption: The first phase culminated in the fall colloquium to discuss innovation in higher education. Topics included dialogue and discourse, race and ethnicity, education in a diverse society and successful global exchanges.

Key outcomes were that delegates and universities wanted more sustained interactions with each other in the form of conferences, workshops, forums and visiting researcher funds. Delegates believed they had just scratched the surface in terms of the interactions and felt that more could be accomplished with deeper discussions. This later realization led to a dialogue workshop at UNSA and several conference presentations, which included those at the American Association of Colleges and Universities (AAC&U) and Association of International Education Administrators (AIEA). There was also a strong sentiment that more could be done in terms of leveraging technology. While the Barzinji Project was primarily focused on in-person travel, delegates felt that the relationships could be sustained through WhatsApp and that discussions, lectures and forums could be held via Zoom.

Caption: A key outcome of the first phase of the Barzinji Project was to have deeper interactions with our partner institutions, such as presenting at conferences.

Leveraging Technology to Sustain Relationships

The Barzinji Project was compelled to realize this last point of leveraging technology as the pandemic hit in early 2020, making in-person travel impossible. Initially, we started to organize virtual forums focused on topics of interest to the various universities, such as “Ramadan Around the World” and “Responses to the COVID-19 Crisis.” Our partner IIUM even organized a virtual conference on “Equality, Religious Harmony and Peace,” demonstrating how productive and fruitful conversations could continue despite the physical distance. The virtual forums eventually led us to explore Collaborative Online International Learning (COIL), where professors from different parts of the world create a shared module in their course to allow their students work on a joint project. The module can last from four to 14 weeks and usually includes an icebreaker where students get to know each other, a shared assignment that they work on and a joint presentation. COIL allows faculty and students to have an international experience without traveling and gives them an opportunity to work with people from around the globe. COIL thus fulfills a key goal of Dr. Barzinji – diversity, equity and inclusion – as it exposes students to various cultures and experiences that ideally lead to more tolerance and understanding. Moreover, the overwhelming majority of students are unable to study abroad because of financial challenges, and COIL provides an international experience for relatively low to minimal cost.

Caption: Our partner IIUM organized a virtual conference during the pandemic demonstrating how technology could be leveraged to sustain partnerships and continue academic discussions.

Additionally, COIL has a strong interdisciplinary focus where faculty from different fields work together on a shared United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG). The aim is not as much in developing a particular discipline but rather working toward a shared goal and solving a world problem. The interdisciplinary nature of COIL fits nicely with Dr. Barzinji’s belief that Muslims and Muslim societies should invest in Islamic Studies but be open to the intellectual accomplishments of Western and American institutions of higher education. For instance, he was founder of the American Journal of Islamic Social Sciences (AJISS) that sought to foster a relationship between traditional Islamic studies and the modern development of social sciences. Shenandoah has now become a recognized leader in COIL, with one of our fellows being selected for an ACE/Fulbright and presenting at various conferences regarding virtual exchange.

Caption: Throughout the pandemic, the Barzinji Institute began to invest heavily in COIL, where two professors from two different universities have their students work on a joint project through platforms like Zoom. COIL fellows ‘Atiah Sidek (IIUM) and Ady Dewey (Bridgewater), pictured above, speak about their faculty “superpowers.”

The Creation of the Barzinji Institute:

As the Barzinji Project grew and Shenandoah University Associate Provost Amy Sarch, Ph.D., took over as the new supervisor (Adrienne Bloss had retired in 2021), we decided to rename the “Barzinji Project” the “Barzinji Institute” to give our activities more permanence. A “project” signals that the initiative was temporary, while an “institute” is more longstanding and research inducive. We further realized that COIL and virtual exchange had become so much a part of our work that we decided to include it in our name: Barzinji Institute for Global Virtual Learning. While we continue to work toward international collaboration to advance higher education, the new name is similar to other programs and offices around the country that have made virtual exchange and COIL central parts of their mission.

In addition to a new name, we included a new service project on the UN SDG of Zero Hunger as a testament to Dr. Barzinji’s commitment to zakat, or alms. Dr. Barzinji was a key donor and advisor to the Foundation for Appropriate and Immediate Temporary Housing, or FAITH, which works on a variety of projects from temporary housing, domestic violence and food security. The new Zero Hunger project will have three universities from around the world – Shenandoah University, Yarmouk University (Jordan) and IIUM – work on alleviating food insecurity in their respective locales and while sharing notes and best practices. The service project complements our COIL program as it is an extracurricular activity within the community, while COIL is primarily academic and within the classroom. Moreover, while the Barzinji Institute retains its core mission of engaging in Muslim-majority countries, it has expanded and become truly global with connections in the Middle East, South America and Western Europe. The global nature of the institute falls in line with Dr. Barzinji’s international business relationships, which ranged from Chile to Zimbabwe.

Caption: The Barzinji Institute continues to expand with new relationships in the Middle East, Western Europe and South America. Here, SU signs a memorandum of understanding with Yarmouk University in Jordan to expand COIL and the Zero Hunger Service Project.

Conclusion

The Barzinji Institute for Global Virtual Learning represents the legacy of Jamal Barzinji by helping to foster understanding between the United States and Muslim-majority countries by having various members visit one another, collaborate and work on joint projects. Through the pandemic, the Barzinji Project invested heavily in virtual exchange, allowing for more sustained and active partnerships. We now plan to expand COIL in general education, develop our Global Service Project and incorporate emerging technologies such as virtual reality. We have now moved from a “project” to an “institute,” demonstrating the permanence of the initiative, and continue to expand in order to put Dr. Barzinji’s mission and vision into action.